From the moment Dennis (Diploma 1968, Ceramics) and Patricia Evans met at a wedding in 1972, they adopted a motto that has shaped every year of their shared life together: “Love Art. Love Life.” It’s a simple phrase — carved onto a Chinese stamp they’ve kept for decades — but for them, it embodies a lifelong devotion to creativity, curiosity, and community.

Now, as AUArts — fondly remembered by Dennis as the Alberta College of Art — approaches its centennial, the Evanses are turning that personal philosophy into a powerful public legacy. In 2026, a new multi-year scholarship they’ve established will begin covering full tuition for deserving students. And that’s just the beginning. Their estate plans include a transformational gift, dedicated to strengthening AUArts into its next century.

“We’ve never wavered from that motto,” Patricia says, idly turning the wedding ring she’s worn since she was 20 — designed by an ACA jewellery student and contemporary of Dennis’s.

“Whenever we talk about people or look at the artwork in our home, it always leads us back to the Alberta College of Art. That school launched our life together. So, this gift simply feels right.”

Wearing the matching ring, Dennis nods. “Our love of life is inseparable from the arts.”

And together, they are ensuring future artists have the same chance to discover that connection.

Why Give? Because Art Builds Thinkers, Problem-Solvers and Leaders

For Dennis, supporting arts education is not an act of nostalgia — it’s an investment in society.

“Art should be mandatory, from elementary to post-secondary,” says the 1968 graduate of the Alberta College of Art (now AUArts), from his home studio in Naramata, B.C.

“The process of creating strengthens every skill — problem-solving, collaboration, focus, attention to detail. It cultivates tolerance and flexibility of thought. The arts make whole people.”

Dennis has seen too many talented young artists deterred by the financial burden of education. “I’ve seen brilliant artists end up working as luggage clerks because they were crippled by debt,” he reflects. “If our scholarships can keep one promising student in school long enough to finish, that’s a success.”

Patricia, who has an art history degree from the University of Houston, agrees wholeheartedly: “If we can ease some of that financial pressure so students can stay focused on their craft, perhaps our legacy is nurturing creative thinkers — people who push society forward.”

Who wouldn’t want to invest in that?

For a Moment, Let’s Step Back

Dennis Evans — one of three sons of Arthur and Lillian — was born in 1946 and raised on a modest Alberta farm near the town of Viking. His upbringing was humble but rich in values: hard work, curiosity in nature, and a deep belief in education. “It’s possible the work ethic of that environment rubbed off on me,” Dennis muses.

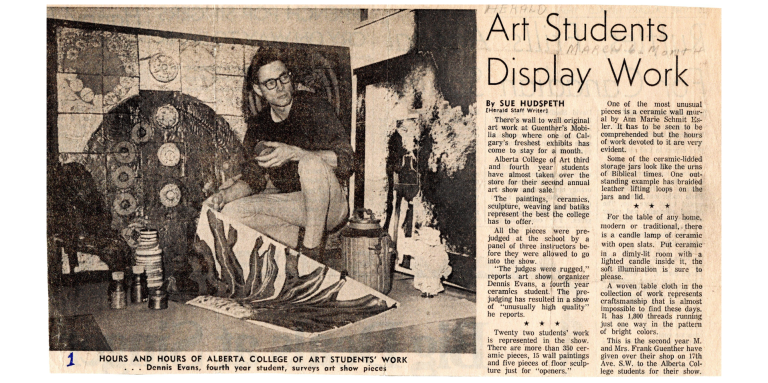

Despite limited means, the Evans household prized learning. When Dennis dreamed of studying graphic arts, his parents were all in. Back in the early 1960s, the college admitted applicants on a first-come basis; the eager 18-year-old “hick,” as he calls himself, lined up early — and got in.

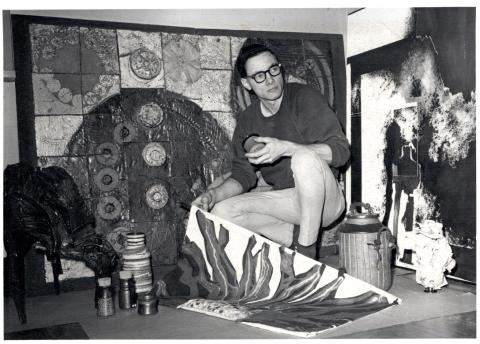

A slight tremor in his hand pushed him out of the intricate precision required in graphic arts and into painting, where he also struggled. Everything, however, changed one day in April when he asked for permission to go outside to paint. He went down to the 10th Street Bridge, on the Bow River. Filling his brush jar with icy water he proceeded to paint an image of the bridge. He was cold, the paint was freezing, but he finished his assignment and returned to the classroom, teeth chattering, for the daily critique. Upon seeing the work, his instructor sprinted down the hall calling others to see the breakthrough that Dennis had. That piece and another of Dennis’s toured the province in the 1968 Alberta Culture tour.

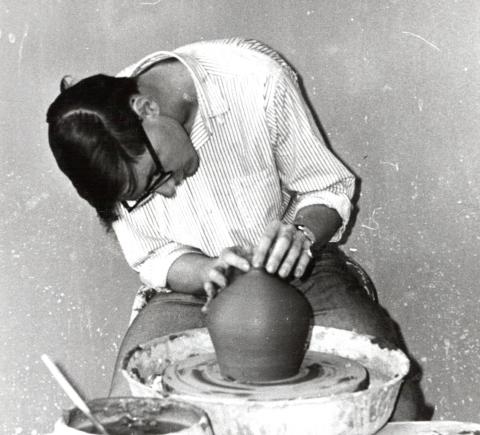

Dennis often wonders what path his life may have taken if, in second year, he hadn’t walked past the ceramics studio. Curiosity propelled him forward and before long he was “smitten.”

Attempting to explain his infatuation, Dennis says: “Clay is a very seductive medium, but at the same time, it’s a tough taskmaster, demanding discipline, respect and hard, physical work to bring it into reality. It will slump, crack and shatter into pieces to remind you,” he explains. “You feel part magician and part alchemist. But, moreover, clay is very humbling. When you push your thumbs into it as you begin to shape your first pinch pot, you are reminded that your hands are not the first that created a shape in this fashion. You connect with humanity through your hands, and that of the first human being who dug up a lump of earth, transforming it into something utilitarian but expressive.”

Dennis’s 60-year-long career was set — as they say, the die was cast. Or, not to mix metaphors, the pot was fired!

The college’s faculty in those years was a who’s-who of Canadian art — Gordon Adaskin, Walter Drohan, Illingworth Kerr, Marion Nicoll, Stanford Perrott, Ron Spickett. Many became lifelong mentors and friends whose expertise contributed to the development of Dennis’s personal artistic style.

Don’t Refuse to Get Your Hands Dirty

Yes, tuition cost only $68 a year in 1966 and the meal plan was all of $10 a month, but Dennis still worked summer jobs for Northwestern Utilities in Viking to afford school. After graduating, Dennis worked for six years at the Canadian Penitentiary in Drumheller, where he was the first professional artist ever hired by such an institution. As an arts and crafts instructor, he taught inmates everything from painting and pottery to silver-smithing and batik — a testament to his well-rounded training.

Hungry for more education, Dennis went on to earn a BFA from the University of Calgary and an MFA from the University of Houston. The 1970s were the golden age of hand-thrown stoneware, and potters like Dennis were in demand. He could throw 400 coffee mugs in a day (a very long day) or 120 casserole dishes — and he did. Full of chutzpah, Dennis hustled his way through every opportunity that came his way: hand-thrown pottery, production management, international development work in Africa, feasibility studies, two start-up companies, a 52-week training program for Siksika students, and eventually a reputation as a kiln-equipment expert. When it came to work, Dennis seized every opportunity.

Wherever opportunity arose, Dennis adapted, learned, and kept creating. Meanwhile, ever his steadfast partner, Patricia continued to work in senior administration within Research Services at the University of Calgary.

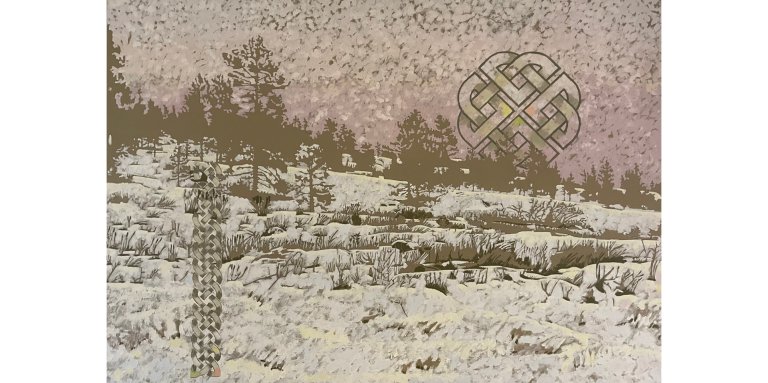

When the couple left Calgary and moved to Naramata, BC in 2006, Dennis finally had something he’d never had before: a dedicated studio. And time to consider a larger purpose.

The Inner Workings of an Artist — and a Legacy

“We knew immediately that we wanted to set up a scholarship fund that would cover a student’s entire tuition for a year,” says Dennis. Frankly, the current cost of tuition shocked him. “I hope these scholarships benefit somebody with great potential who may have fallen by the wayside because of financial needs."

“I’m hoping our scholarships keep students in university long enough to finish their four-year commitment and find more opportunities with a degree."

“Being an artist takes courage and chutzpah,” Dennis says. “You need business sense. You need to read society. You need to translate ideas onto canvas or clay, then market them and bring them to the public.”

Patricia adds, “If we can help young artists stay the course, maybe our legacy is supporting the minds that will shape cultural change.”

That ambition fits perfectly with a broader vision taking shape in Calgary: the AUArts centennial in 2026, the Glenbow Museum’s reopening, the emergence of the Werklund Centre (formerly Arts Commons) as a renewed cultural hub. The city is poised for an artistic renaissance.

“People travel to Paris for the Louvre and to London for the V&A’s ceramics collection,” Patricia says. “We know that art and architecture is what people flock to in every major city. Let’s make that happen here.”

An Open Door for Those Yet to Come

As AUArts steps into its next century, the Evanses’ generosity ensures new voices, new visions and new talents have room to rise.

Their motto — Love Art. Love Life. — is no longer just a philosophy.

It is a door they are holding open.

And they are inviting future generations to walk through.

In 2026, Alberta University of the Arts (AUArts) will celebrate 100 years of shaping the creative landscape in Alberta and beyond. To mark this historic occasion, AUArts is launching Centennial Scholarships — an ambitious initiative to provide tuition-free scholarships for the next generation of diverse artists, craftspersons and designers.